Stopping painkillers after weeks or months of use triggers a predictable set of physical and psychological symptoms that can feel overwhelming.

In the fentanyl era, withdrawal often lasts longer and feels more intense than classic timelines suggest, with acute symptoms typically resolving in 4 to 10 days for short-acting opioids but extending beyond two weeks for long-acting agents and frequently behaving unpredictably when fentanyl is involved.

This article explains what to expect during painkiller withdrawal, how modern detox strategies reduce risk, and why linking to ongoing medication treatment is essential to prevent relapse and overdose.

What Happens During Painkiller Withdrawal?

Opioid withdrawal results when chronic exposure to painkillers is reduced or stopped, causing a deficit in mu-opioid receptor signaling and triggering a hyperadrenergic state.

The body reacts with a constellation of autonomic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and neuropsychiatric symptoms. While uncomfortable and distressing, adult opioid withdrawal is rarely life threatening in isolation, though catecholamine surges can stress comorbid conditions.

Core withdrawal symptoms include tachycardia, hypertension, sweating, dilated pupils, agitation, anxiety, intense cravings, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, muscle aches, chills, dysphoria, irritability, insomnia, and restlessness.

The intensity and timing depend on the opioid’s half-life, receptor dynamics, dose, duration of use, and individual physiology.

Clinicians use validated tools to measure severity. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) is an observer-rated instrument scoring objective and subjective signs to stratify severity and guide treatment dosing.

A COWS score of 8 or higher indicates at least mild to moderate withdrawal, with many protocols preferring 12 or above before standard buprenorphine initiation to reduce precipitated withdrawal risk. The Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) complements COWS as a patient-reported measure, with 2 to 4 points considered a clinically meaningful change.

Painkiller Withdrawal Timeline by Opioid Type

For pharmaceutical-grade opioids, withdrawal onset correlates with pharmacokinetics. Short-acting painkillers such as heroin, morphine, hydrocodone, and immediate-release oxycodone typically produce moderate withdrawal within 12 to 16 hours after the last dose.

Intermediate-acting formulations onset around 17 to 24 hours. Long-acting opioids like methadone onset later, around 30 to 48 hours or more.

These estimates assume known products. Illicit supplies contaminated with unknown substances, notably fentanyl analogues, can delay onset or alter course, rendering the clock less reliable than symptom-triggered approaches.

The British Columbia provincial OUD guideline emphasizes relying on symptoms and objective signs rather than rigid abstinence clocks, especially important with fentanyl-adulterated supplies.

Short-Acting Opioids

Withdrawal from short-acting painkillers often begins within 8 to 24 hours, commonly around 12 to 16 hours for pharmaceutical-grade products.

Symptoms typically peak over 24 to 72 hours and abate over 4 to 10 days. This timeline remains broadly valid for known pharmaceutical opioids.

Long-Acting Opioids

Methadone’s long and variable half-life results in later-onset, prolonged withdrawal. Classic resources cite onset around 24 to 72 hours and duration of 10 to 20 days or more, with peak often later than short-acting agents.

Clinically, many protocols require 72 hours or more of abstinence before standard buprenorphine induction when transitioning from methadone to reduce precipitated withdrawal risk.

Buprenorphine itself, as a partial agonist with high receptor affinity, produces a relatively delayed and often milder abstinence syndrome upon cessation compared with full agonists.

Its long half-life means abrupt cessation can yield subacute symptoms that persist, complicating a simple stopwatch narrative.

How Fentanyl Changes the Withdrawal Picture?

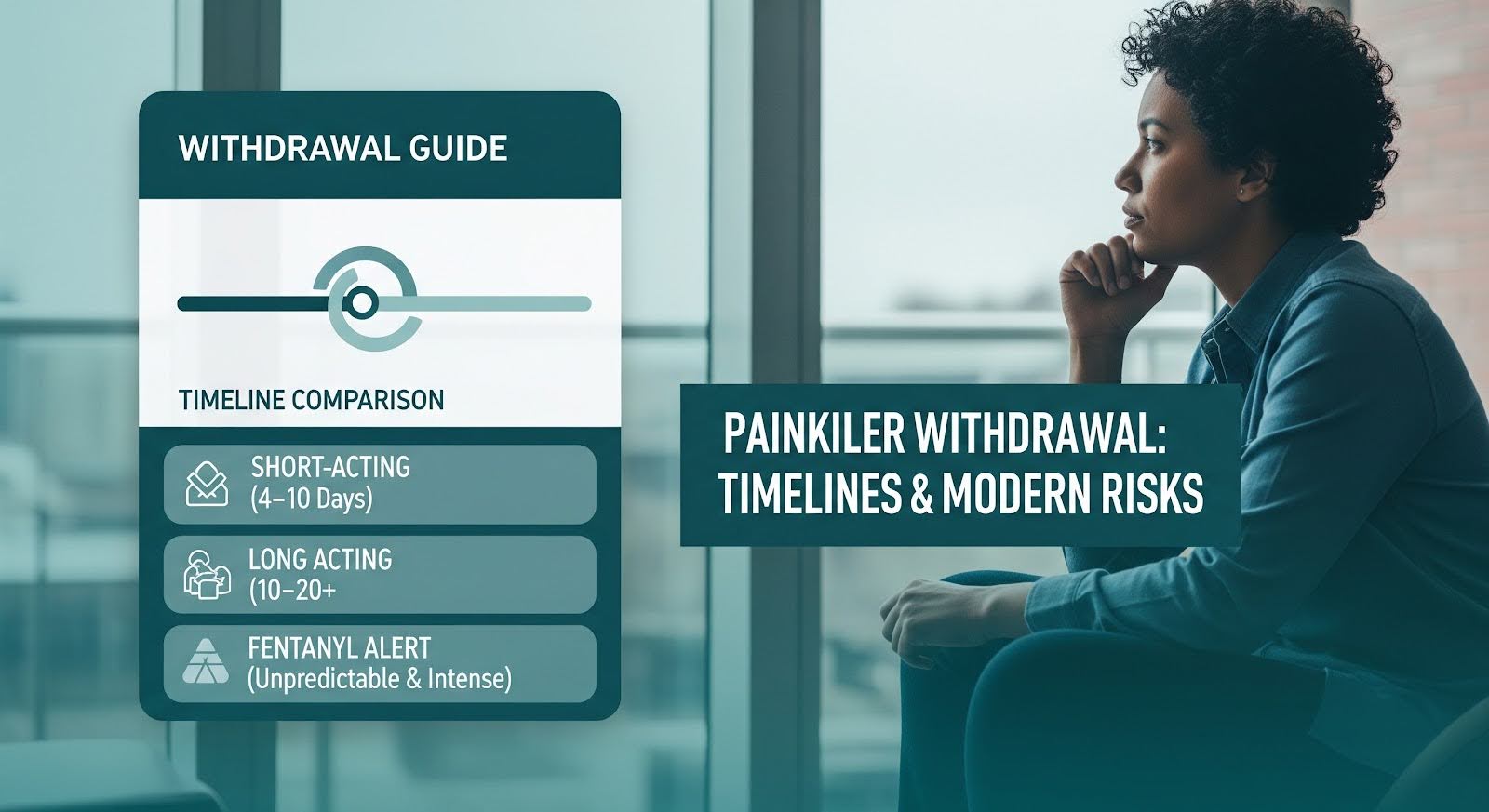

Fentanyl’s lipophilicity enables rapid brain uptake but also extensive distribution to muscle and fat, with slow redistribution and elimination. Chronic, high-frequency use typical in illicit contexts leads to tissue reservoirs and protracted renal clearance.

Urine fentanyl and norfentanyl can remain detectable for a week or more following last use in frequent users, translating into ongoing receptor occupancy even after subjective withdrawal begins.

Clinically, this means withdrawal may onset around 8 to 24 hours, but the intensity and duration are more variable. A subset experiences prolonged or rebound symptoms as fentanyl trickles out of tissue stores.

Standard abstinence times to be safe for buprenorphine, such as 12 to 24 hours, understate risk. In practice, 24 hours or more is often necessary, and even prolonged abstinence may not prevent precipitated withdrawal.

A quasi-experimental comparison under identical morphine stabilization protocols before versus after fentanyl market penetration found the fentanyl-era cohort exhibited higher peak withdrawal scores on multiple days.

A larger proportion rated withdrawal as severe on days 2 through 5, with 48 percent versus 16 percent on day 2, 47 percent versus 8 percent on day 3, 37 percent versus 6 percent on day 4, and 27 percent versus 6 percent on day 5, suggesting more intense and persistent withdrawal at least through day 5 or 6.

These observations underpin modern recommendations to verify definite withdrawal with COWS of 8 to 12 or higher with objective signs and, when risk is high or uncertainty persists, to use microinduction or delay initiation with supportive medications rather than forcing the clock.

Precipitated Withdrawal and Safer Induction Strategies

Buprenorphine is a high-affinity partial opioid agonist. When administered in the presence of full agonists such as fentanyl, methadone, or heroin, it displaces them and reduces net receptor activation, triggering an abrupt precipitated withdrawal.

This is typically most likely when initiation occurs before moderate to severe withdrawal is present. In fentanyl users, even standard thresholds can fail due to persistent tissue-derived fentanyl causing ongoing receptor activation.

In a retrospective three-hospital cohort of emergency department and inpatient initiations, precipitated withdrawal incidence was 11.5 percent overall and 16.3 percent among those with confirmed fentanyl.

Higher urine fentanyl concentration of 200 nanograms per milliliter or more and body mass index of 30 or higher were associated with increased precipitated withdrawal odds.

Low-Dose and Microinduction Approaches

Low-dose initiation, or microinduction, starts buprenorphine in microdoses while continuing a full agonist, either prescribed or ongoing use, titrating buprenorphine upward over days until sufficient receptor occupancy is achieved, then tapering the full agonist.

Hospital cohorts with intravenous or sublingual low-dose protocols show high completion and acceptable tolerability, with 91.5 percent completion and 72.9 percent meeting tolerability criteria in a hospitalized cohort with prevalent fentanyl exposure.

Ultra-rapid low-dose induction with concurrent short-acting full agonist gives small, frequent sublingual buprenorphine doses with as-needed hydromorphone to treat breakthrough symptoms, achieving therapeutic buprenorphine maintenance within 24 to 72 hours and facilitating discharge. Case series demonstrate good tolerability and discharge on therapeutic doses within 1 to 3 days.

A simplified rapid low-dose induction using standard 8-2 milligram films in an outpatient safety-net clinic achieved 77.8 percent successful initiation at one week among fentanyl-using patients, with good tolerability and patient-friendly logistics.

This same-day, approximately 8-hour schedule minimizes complexity and access barriers of multi-formulation microdosing.

Rapid induction onto extended-release buprenorphine after overdose uses brief sublingual buprenorphine to prime receptors then administers a 300-milligram extended-release injection within 7 days of emergency department presentation.

A case series observed no precipitated withdrawal or serious adverse events during induction and no repeat overdoses or deaths within 6 months among inductees.

Detox Risks and the Importance of Ongoing Treatment

Withdrawal management, or detox, refers to short-term, non-bridged taper processes that do not transition to long-term opioid agonist therapy.

Contemporary guidelines strongly discourage detox-only because it increases relapse risk, risky post-discharge behaviors, and overdose deaths, particularly with loss of tolerance.

Opioid agonist therapy with buprenorphine, methadone, slow-release oral morphine, or injectable options consistently outperforms detox-only in retention, abstinence, and mortality.

A Massachusetts detox cohort of 30,681 patients and 61,819 detox episodes from 2012 to 2014 found that 12 months post-detox, 41 percent received medication for opioid use disorder with a median of 3 months, 35 percent received residential treatment with a median of 2 months, and 13 percent received both with a median of 5 months.

On-treatment analyses showed all-cause mortality was 66 percent lower with medication versus no treatment, 37 percent lower with residential treatment, and 89 percent lower with both. With-discontinuation analyses showed medication reduced mortality by 48 percent, residential by 24 percent, and both by 79 percent. Results were similar for opioid-related overdose mortality.

A scoping review of hospitalization and linkage found inpatient medication initiation associated with lower odds of discharge against medical advice, lower 30-day readmission, and higher post-discharge medication adherence.

Adherent patients had fewer emergency department visits and opioid overdoses in the 90 days post-discharge. Initiating medication within 7 days of an opioid use disorder-related hospital visit was associated with a 37 percent reduction in adjusted odds of fatal or nonfatal overdose at 6 months.

Polysubstance Risks: Xylazine and Medetomidine

Xylazine, a non-opioid alpha-2 agonist, is increasingly detected in illicitly manufactured fentanyl-involved overdose deaths.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis across 21 jurisdictions, including Georgia, documented a 276 percent rise in the monthly proportion of fentanyl-involved deaths with xylazine detected from January 2019 at 2.9 percent to June 2022 at 10.9 percent.

Clinical cohorts in Philadelphia demonstrated feasibility of multimodal fentanyl and xylazine withdrawal protocols, including microdosed buprenorphine, short-acting opioids, and adjuncts, with reductions in median COWS from 12 to 4 and low rates of discharge against medical advice at 3.9 percent versus baseline 10.7 percent.

Medetomidine, an emerging non-opioid sedative adulterant, was detected in 2024 to 2025 in Philadelphia cohorts. Withdrawal and intoxication phenotypes were associated with variable xylazine co-detection and universal fentanyl and norfentanyl detection.

Paired intoxication and withdrawal samples over 13 to 48 hours showed rapid elimination of fentanyl, norfentanyl, and medetomidine, creating rapidly shifting toxidromes that complicate timing of induction and adjunctive management.

Adjunctive Medications: Benefits and Limits

Non-opioid symptomatic management such as alpha-2 agonists like clonidine or lofexidine, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and sleep aids can reduce distress.

However, increasing evidence suggests that fentanyl-related withdrawal often responds poorly to non-opioid regimens alone, introductory methadone, or standard slow-release oral morphine dosing. This reinforces a medication-centered strategy rather than short-term withdrawal management.

Gabapentinoids, including gabapentin and pregabalin, have been explored as adjuncts in some withdrawal contexts, but growing literature highlights misuse, dependence, and withdrawal syndromes upon discontinuation, including neuropsychiatric phenomena such as transient psychosis and seizures in chronic kidney disease.

Given widespread misuse among populations with opioid use disorder and their potential to potentiate respiratory depression when combined with opioids, routine gabapentinoid use for opioid withdrawal should be approached cautiously, targeted to clear indications such as neuropathic pain with safeguards.

What to Expect: A Practical Timeline

Acute withdrawal duration varies by agent, dosing pattern, and individual physiology. In contemporary practice, short-acting opioids such as heroin and immediate-release oxycodone typically produce moderate withdrawal within 8 to 24 hours, with acute symptoms often resolving within 4 to 10 days.

Long-acting opioids such as methadone begin later, around 30 to 48 hours or more, and last longer, often 10 to 20 days or more.

Fentanyl frequently behaves as a long-acting agent, with protracted and unpredictable timelines due to tissue sequestration and slow elimination, making abstinence-based buprenorphine initiation riskier than classical teaching suggests.

Duration estimates must be framed as ranges, with explicit caveats for fentanyl, and induction should be guided by objective withdrawal scores and patient experience, not rigid clock time.

Sleep disturbance is prevalent at treatment entry and often persists, relates to craving, and may contribute to relapse. Extended-release naltrexone may be associated with lower persistent insomnia than buprenorphine in some trials.

Sleep-disordered breathing is common in methadone-maintained patients. Preclinical work suggests sleep-targeted approaches such as orexin antagonists could mitigate relapse risk, though human translational studies are needed.

Why Medication Treatment Saves Lives?

To reduce harm and improve retention, clinicians should avoid detox-only pathways, leverage microinduction and flexible dosing, including high-dose strategies when indicated and monitored, and identify and treat persistent sleep disturbance as part of post-acute care.

This approach better reflects the high-potency, adulterated opioid supply characterizing the current landscape and aligns with the strongest and most recent evidence from emergency, inpatient, and primary care settings.

The question is not merely how long withdrawal lasts but how to help patients get through it safely and stay well afterward. The data recommend long-term opioid agonist therapy, flexible initiation, and sleep-targeted aftercare as core elements.

Detox without transition to maintenance medication is a preventable pathway to death in the fentanyl era. Systems that fail to adapt are taking unacceptable risks with patients’ lives.

If you or someone you care about is facing painkiller withdrawal, compassionate, evidence-based support can make all the difference. Reach out to explore Thoroughbred Wellness and Recovery’s medication treatment options that prioritize safety, dignity, and lasting recovery.