Heroin withdrawal feels overwhelming, but understanding what to expect can reduce fear and help you plan.

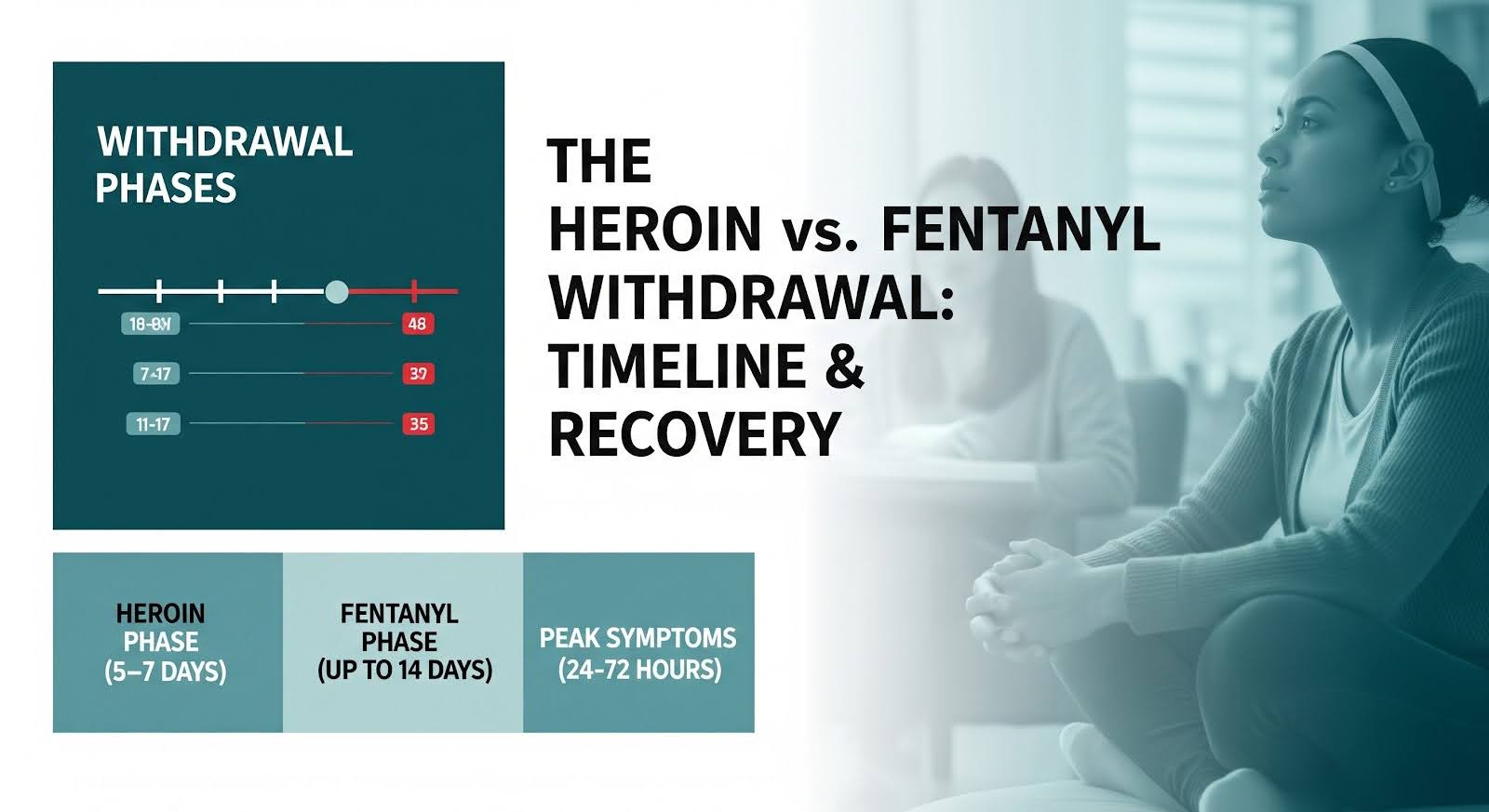

Acute withdrawal from short‑acting heroin typically lasts five to seven days, though fentanyl exposure can extend symptoms to two weeks or more.

This article explains the withdrawal timeline, common symptoms, medical risks, and evidence‑based treatments that make detox safer and more successful.

What Happens During Heroin Withdrawal?

Heroin withdrawal is the body’s response when you stop using after physical dependence has developed. Within hours of your last dose, your nervous system rebounds from opioid suppression, triggering a cascade of uncomfortable physical and emotional symptoms.

The syndrome is rarely fatal on its own, but it drives intense cravings and relapse risk, and complications like dehydration or aspiration can become serious without medical support.

The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale quantifies severity using eleven observable signs, from pupil dilation and sweating to restlessness and gastrointestinal distress.

Scores guide treatment decisions: mild withdrawal (5–12 points) may be managed with comfort medications, while moderate to severe scores (13 or higher) often warrant medications for opioid use disorder to prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Why Fentanyl Changes the Picture?

Today’s illicit opioid supply is dominated by fentanyl, not traditional heroin. Fentanyl’s high potency and prolonged tissue retention can delay withdrawal onset, push peak symptoms to three to seven days after last use, and extend the acute phase beyond the classical week‑long window.

Many people who believe they are detoxing from heroin are actually withdrawing from fentanyl, which complicates timing for medications like buprenorphine and increases the risk of precipitated withdrawal if treatment starts too early.

Heroin Withdrawal Symptoms: What to Expect?

Symptoms unfold in predictable waves, though individual experiences vary based on use patterns, opioid type, and overall health.

Early symptoms (6–12 hours for heroin; later for fentanyl):

- Anxiety and restlessness

- Yawning and tearing

- Sweating and runny nose

- Muscle aches

- Dilated pupils

- Insomnia

Peak symptoms (24–72 hours for heroin; 3–7 days for fentanyl):

- Severe muscle and bone pain

- Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- Abdominal cramping

- Rapid heartbeat and elevated blood pressure

- Chills alternating with sweats

- Intense cravings and agitation

Late acute phase (days 3–10):

- Gradual improvement in physical symptoms

- Persistent insomnia and fatigue

- Mood swings and irritability

- Low appetite

- Episodic cravings

Protracted symptoms (weeks to months):

- Anxiety and depression

- Sleep disturbances

- Impaired concentration

- Low energy and anhedonia

- Ongoing cravings

The DSM‑5 diagnostic criteria for opioid withdrawal require clinically significant distress or impairment alongside these physical signs, underscoring that withdrawal is a medical syndrome deserving structured care, not willpower alone.

How Long Does Heroin Detox Take?

For short‑acting heroin without fentanyl involvement, acute withdrawal usually resolves in four to ten days, with most people feeling substantially better by day five to seven.

However, in fentanyl‑dominant markets, many patients experience a longer course: onset delayed to 24–72 hours, peak intensity at three to seven days, and meaningful symptoms persisting for seven to fourteen days or more.

Planning for up to two weeks of significant discomfort in fentanyl contexts is realistic and reduces the risk of premature discharge from care.

Protracted symptoms, sleep problems, mood instability, cognitive fog, and cravings, can linger for weeks to months and are best managed with ongoing medications for opioid use disorder, therapy, and structured recovery support.

| Phase | Typical Timing (Heroin) | Prominent Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Early | 6–24 hours | Anxiety, sweating, muscle aches, yawning, dilated pupils |

| Peak | 24–72 hours | Severe pain, nausea/vomiting/diarrhea, tachycardia, intense cravings |

| Late Acute | Days 3–10 | Improving physical symptoms; insomnia, fatigue, mood swings persist |

| Protracted | Weeks–months | Anxiety, depression, low energy, impaired focus, cravings |

Can You Die from Heroin Withdrawal?

Heroin withdrawal itself is rarely fatal, but serious complications can occur. The greatest lethal risk is not the withdrawal syndrome but what follows: relapse after tolerance has dropped. Returning to pre‑detox doses with reduced tolerance is a leading cause of post‑detox overdose deaths.

Direct withdrawal‑related deaths are uncommon but documented, typically through:

- Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances: Persistent vomiting and diarrhea can cause severe dehydration and hypernatremia, stressing the heart and kidneys, especially in people with cardiovascular disease or other comorbidities.

- Aspiration: Repeated emesis raises the risk of inhaling stomach contents, which can lead to aspiration pneumonia.

- Cardiac stress: Autonomic instability, tachycardia and hypertension, can unmask underlying heart conditions.

- Polysubstance withdrawal: Co‑withdrawal from alcohol or benzodiazepines can trigger seizures, compounding risk.

Rapid or anesthesia‑assisted detox methods have been linked to serious adverse events, including arrhythmias, pulmonary edema, and deaths, and are not recommended by expert consensus.

Medically supervised detox with medications for opioid use disorder is the safest, most effective approach.

Evidence‑Based Treatment for Heroin Withdrawal

The most effective way to manage withdrawal and reduce long‑term risks is to initiate medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) during or immediately after detox.

Buprenorphine and methadone not only ease acute symptoms but also lower relapse and overdose mortality when continued as maintenance treatment.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that relieves withdrawal and cravings without the euphoria of full agonists. It is the preferred first‑line medication for many patients and can be started in emergency departments, outpatient clinics, or inpatient settings.

Timing is critical: buprenorphine should begin only when moderate withdrawal is evident (typically a Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale score of 6 or higher) to reduce the risk of precipitated withdrawal, a sudden worsening of symptoms caused by displacing fentanyl from opioid receptors too early.

In fentanyl‑exposed patients, two strategies have proven helpful:

- High‑dose buprenorphine rescue: If precipitated withdrawal occurs, administering higher cumulative doses of buprenorphine rapidly overcomes receptor imbalance and relieves symptoms safely under medical supervision.

- Micro‑induction (Bernese method): Overlapping small, escalating doses of buprenorphine with a full agonist opioid minimizes precipitated withdrawal risk and is particularly useful in inpatient settings for patients with heavy fentanyl use or complex medical needs.

Methadone

Methadone is a full opioid agonist that provides robust relief of withdrawal and cravings. It is especially effective for patients with high opioid tolerance or those who do not tolerate buprenorphine.

Methadone initiation requires enrollment in a federally regulated opioid treatment program and careful dose titration to avoid QT prolongation and other risks, but it remains a cornerstone of evidence‑based care.

Adjunctive Medications

Non‑opioid medications target specific symptoms and improve comfort during detox:

- Alpha‑2 agonists (clonidine, lofexidine) reduce sweating, anxiety, and rapid heart rate.

- Antiemetics control nausea and vomiting.

- Antidiarrheals (loperamide) ease gastrointestinal distress.

- NSAIDs and acetaminophen relieve muscle and bone pain.

- Sleep aids (trazodone) address insomnia.

These adjuncts improve tolerability but do not replace MOUD for long‑term outcomes.

Multimodal Protocols for Complex Withdrawal

In markets where fentanyl is adulterated with sedatives like xylazine, withdrawal can include pronounced sympathetic activation, severe tachycardia, hypertension, and protracted vomiting.

A multimodal emergency department protocol combining buprenorphine, alpha‑2 agonists, pain management, and symptom‑targeted medications reduced withdrawal severity and patient‑directed discharges in one cohort, suggesting that flexible, comprehensive care improves retention and comfort in complex cases.

Risks After Detox: The Overdose Window

The most dangerous period surrounding heroin withdrawal is not the acute phase but the days and weeks after detox, when tolerance has dropped. Returning to opioid use at previous doses can be fatal.

This risk is why detoxification alone, without transition to MOUD, is associated with higher relapse and mortality rates.

Harm reduction strategies are essential:

- Naloxone access: Carry naloxone and educate family or friends on how to use it.

- Never use alone: Use with someone present or via virtual overdose prevention services.

- Start low: If relapse occurs, use a much smaller dose than before detox.

- Fentanyl test strips: Where legal, test substances for fentanyl and other adulterants.

Continuing buprenorphine or methadone maintenance after detox is the most effective way to prevent relapse and overdose.

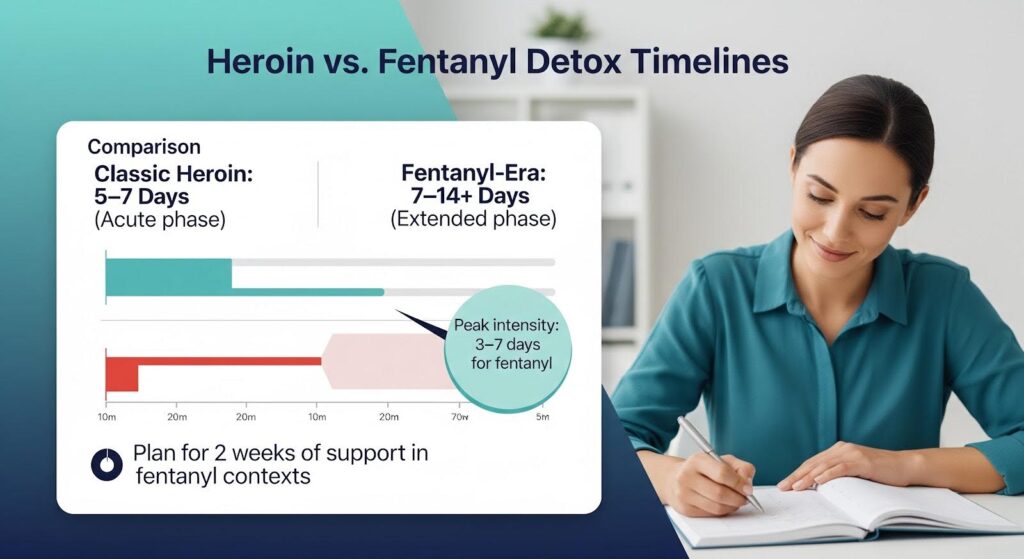

What About Xylazine and Other Adulterants?

Xylazine, a veterinary sedative, has been detected in fentanyl supplies in some U.S. cities, prompting concerns about a distinct “xylazine withdrawal syndrome.”

However, recent human cohort studies have not identified a consistent, reproducible xylazine withdrawal pattern. Symptoms previously attributed to xylazine, such as agitation, tachycardia, and hypertension, often overlap with opioid withdrawal or other co‑exposures.

In Atlanta, drug surveillance data from mid‑2025 showed zero detections of xylazine or medetomidine in recent law enforcement seizures, suggesting that local withdrawal protocols should prioritize fentanyl‑focused management while remaining alert for novel benzodiazepines and other adulterants.

Clinicians should treat symptoms as they present, using multimodal care when autonomic instability or protracted vomiting suggests sedative involvement, rather than assuming a separate withdrawal syndrome.

Medical Detox vs. Outpatient Support

Medical detox provides 24‑hour supervision, intravenous hydration, and immediate access to medications and monitoring.

It is appropriate for people with severe withdrawal, medical comorbidities, polysubstance use, or limited social support. Detox programs should transition patients to outpatient MOUD and counseling to sustain gains.

Outpatient detox with MOUD initiation is safe and effective for many patients, especially when withdrawal is mild to moderate and social support is in place.

Emergency departments increasingly offer buprenorphine initiation, which improves engagement and reduces relapse compared to referral alone.

Choosing the right setting depends on withdrawal severity, medical history, substance use patterns, and personal circumstances. Both pathways should lead to ongoing MOUD and recovery support.

Protracted Withdrawal and Long‑Term Recovery

After acute symptoms resolve, many people experience weeks to months of protracted withdrawal: anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, low energy, impaired concentration, and cravings.

This phase is sometimes called post‑acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS), though the term is not a formal diagnosis and evidence varies by substance.

Managing protracted symptoms requires:

- Continued MOUD: Buprenorphine or methadone at adequate doses suppresses cravings and stabilizes mood.

- Psychotherapy: Cognitive‑behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and trauma‑focused approaches address underlying issues and build coping skills.

- Sleep hygiene: Consistent routines, limiting screens, and sleep aids when needed.

- Structured activities: Work, school, exercise, and peer support provide purpose and reduce isolation.

- Treatment of co‑occurring mental health conditions: Anxiety, depression, and PTSD are common and respond to integrated care.

Protracted symptoms improve non‑linearly, good days and bad days are normal. Patience, support, and ongoing treatment reduce relapse risk and support functional recovery.

Coding and Surveillance: Improving Data Quality

Accurate diagnostic coding helps track withdrawal trends, allocate resources, and evaluate treatment effectiveness. The ICD‑10‑CM codes for opioid withdrawal are:

- F11.23: Opioid dependence with withdrawal (billable, effective October 2025).

- F11.93: Opioid use, unspecified with withdrawal (billable, effective October 2025).

These codes exclude opioid intoxication and poisoning, improving specificity when isolating withdrawal cohorts for research and quality improvement.

Pairing clinical severity metrics like the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale with these codes enhances surveillance in emergency and inpatient settings.

Policy and Access: Georgia’s Landscape

Georgia has expanded access to medications for opioid use disorder through several initiatives:

- Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP): Georgia’s PDMP requires reporting of dispensed controlled substances within 24 hours and supports prescriber queries to inform treatment decisions and reduce overlapping prescriptions.

- E‑prescribing rules: Georgia permits electronic transmission of prescriptions directly from prescribers or compliant formatters, with DEA rules governing controlled substances and teleprescribing.

- Naloxone standing order and fentanyl test strips: Georgia’s standing order for naloxone and legalization of fentanyl test strips support harm reduction statewide.

- Opioid treatment programs (OTPs): Federal guidelines emphasize safe methadone and buprenorphine practices, patient‑centered dosing, and integration with counseling and recovery support.

Atlanta‑area health systems, including Emory and Grady, have launched programs to expand MOUD access. The REAL TIME program supports rural emergency departments via telehealth and the Georgia Poison Center’s on‑call toxicologist, assisting with acute withdrawal and buprenorphine initiation.

Grady’s Medication for Alcohol and Opioid Treatment Clinic provides outpatient MOUD, counseling, and wraparound services, with recent settlement funds expanding capacity.

Payer policies from UnitedHealthcare and Aetna cover extended‑release buprenorphine formulations like Sublocade and Brixadi under specified criteria, offering an option to reduce early relapse risk after short stabilization on sublingual buprenorphine.

Practical Steps for Safe Withdrawal

If you or someone you care about is facing heroin withdrawal, these steps can improve safety and outcomes:

1. Seek medical evaluation: A brief assessment can determine the appropriate level of care and identify comorbidities.

2. Start MOUD early: Buprenorphine or methadone initiated during withdrawal reduces symptoms, cravings, and relapse risk.

3. Stay hydrated: Drink fluids and replace electrolytes; seek medical attention if vomiting or diarrhea is severe.

4. Use adjunctive medications: Ask about clonidine, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and pain relievers to ease specific symptoms.

5. Plan for continuity: Schedule outpatient MOUD follow‑up, counseling, and peer support before leaving detox.

6. Carry naloxone: Obtain naloxone and educate loved ones on overdose reversal.

7. Avoid rapid detox: Anesthesia‑assisted detox carries serious risks and is not recommended.

8. Address co‑occurring conditions: Treat anxiety, depression, trauma, and other mental health issues alongside opioid use disorder.

Why is MOUD the Standard of Care?

Decades of research confirm that buprenorphine and methadone are superior to detoxification alone for retention in treatment, reduction in illicit opioid use, and lower overdose mortality.

Short‑term detox without ongoing MOUD is associated with high relapse rates and increased overdose risk due to lost tolerance.

MOUD is not “replacing one drug with another”, it is evidence‑based medicine that stabilizes brain chemistry, reduces cravings, and allows people to rebuild their lives.

Combined with counseling, peer support, and holistic therapies, MOUD offers the best chance for long‑term recovery.

Moving Forward with Confidence

Heroin withdrawal is uncomfortable and challenging, but it is manageable with the right support. Understanding the timeline, roughly one week for heroin, up to two weeks or more for fentanyl, helps set realistic expectations. Knowing the symptoms, risks, and evidence‑based treatments empowers you to make informed decisions and advocate for quality care.

The greatest danger is not the withdrawal itself but the period after detox, when tolerance is low and relapse risk is high. Medications for opioid use disorder, harm reduction education, and ongoing recovery support dramatically reduce this risk and improve long‑term outcomes.

If you or a loved one is ready to take the next step, reach out to Thoroughbred’s medical detox program that offers compassionate, evidence‑based care and a clear path to sustained recovery.